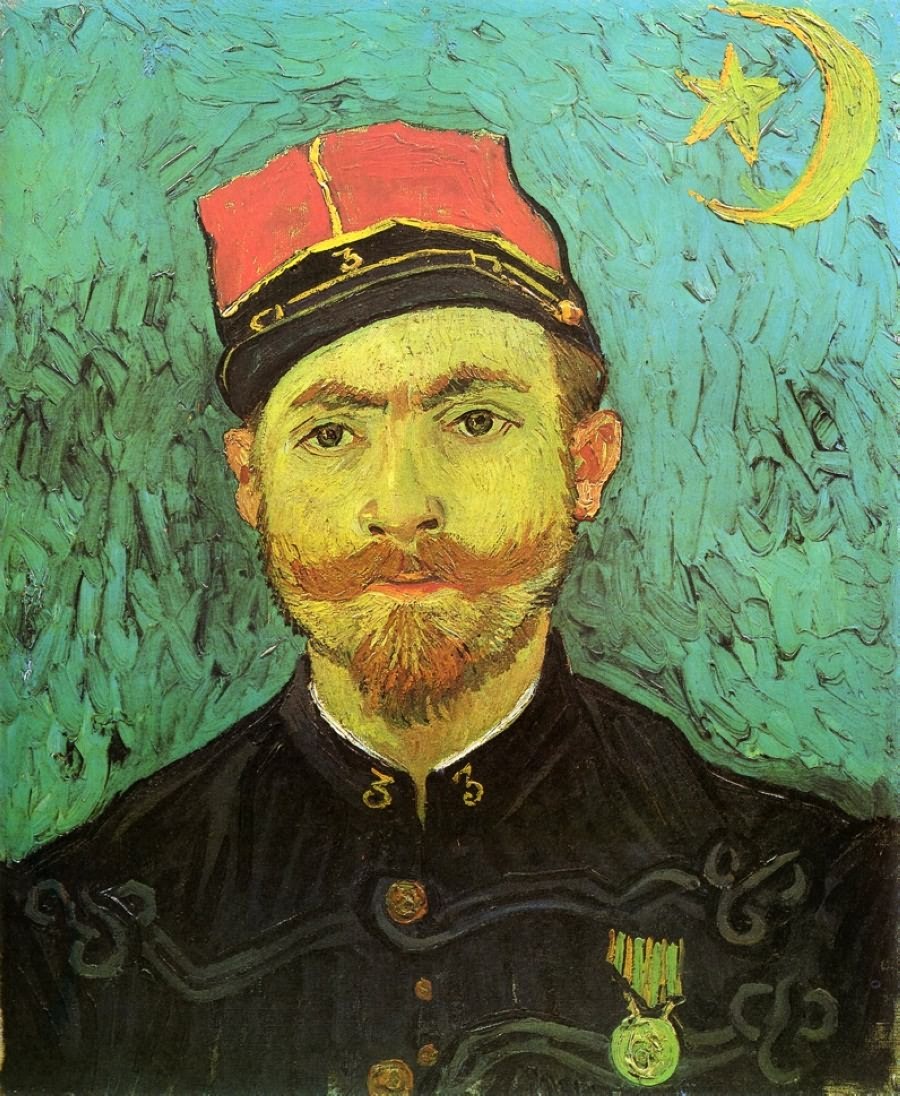

Portrait of Milliet, Second Lieutnant of the Zouaves

Appreciation

Portrait of Milliet, Second Lieutnant of the Zouaves Nederland Vincent van Gogh Gallery and Appreciation

Paul-Eugène Milliet was a 2nd Lieutenant at the 3rd Zouave Regiment which had quarters at the Caserne Calvin located on Boulevard des Lices in Arles. Vincent van Gogh gave him drawing lessons, and in return Milliet took a roll of paintings by Van Gogh to Paris, when in mid August he was passing the French capital on his way to the North, where Milliet spent his holidays. On his return to Arles, at the end of September 1888, Milliet handed over a batch of Ukiyo-e woodcuts and other prints selected by Vincent's brother Theo from their collection. In the days that followed Vincent executed this portrait of Milliet.

In the first version of Van Gogh's Bedroom, executed in October 1888, Milliet's portrait is shown hanging to the right of the portrait of Eugène Boch.

Decades later, when Milliet had retired to the 7th arrondissement in Paris, his memories of Van Gogh were recorded by Pierre Weiller, at this time living on lease in a building owned by Milliet, and published in 1955, after Milliet's death.

This painting depicts Paul-Eugène Milliet, second lieutenant in the third regiment of the Zouaves. Milliet and Vincent van Gogh became friends in 1888 when both men were in Arles, France.

Biography of Milliet

Paul-Eugène Milliet was the son of a military policeman and lived most of his life as a soldier. Milliet grew up in army barracks and his military career had been progressing well by the time he was temporarily stationed in Arles in 1888. Milliet's regiment had just returned from Tonkin (then French Indochina, now the region around the Gulf of China in Vietnam). During that campaign Milliet had contracted an illness and looked forward to convalescing in the south of France.

In August Milliet made a brief journey to Paris and was entrusted with thirty six of Vincent's studies to give to the artist's brother, Theo. He stayed in Arles for the rest of the summer and into early autumn, finally leaving around 1 November for Algeria. In the years to follow Milliet had a distinguished career in the military, serving in Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco and during the First World War. He retired with the rank of lieutenant-colonel and had received the decoration of Commander of the Légion d'Honneur.

In 1930 a writer, Pierre Weiller, was looking for a new apartment in Paris and went to meet with his prospective landlady. Upon arrival Weiller was met by the landlady's husband, none other than Paul-Eugène Milliet, by then retired from the military. Weiller quickly recognized Milliet and interviewed him about his acquaintance with Vincent van Gogh. He later wrote an article "We've Tracked Down Van Gogh's Zouave" based on that interview.

Milliet died in Paris during the German occupation of World War II.

The Zouaves

The Zouaves were a group of light infantry personnel in the French army. The Zouave soldiers were mainly from Algeria and, though European, their uniforms showed arabesque influences. In addition to his portrait of Milliet, Vincent van Gogh would depict another Zouave in five other works:

The Seated Zouave

The Zouave (Half Length)

The Zouave (Half Length)

Zouave Sitting, Whole Figure

Zouave, Half-Figure

Interestingly, there was an American offshoot of the Zouaves that few know about today. During the American Civil War, regiments on both sides often chose special names and uniforms for themselves. On the Union side there were a number of regiments that modeled themselves after France's Zouaves. They wore short blue jackets, yellow shirts and red pantaloons and were often seen in battle around 1861. By 1863, however, the American Zouave regiments became more uncommon.

Relationship with Van Gogh

Paul-Eugène Milliet was atypical of many who chose a life long career in the military. Milliet had a keen interest in art and was enthusiastic about painting and drawing. It was only natural that he and Van Gogh would gravitate toward one another in Arles. Van Gogh wrote to Emile Bernard:

I know a second lieutenant in the Zouaves here; his name is Milliet. I give him drawing lessons--with my perspective frame--and he is beginning to do some drawings and, honestly, I've seen far worse. He is keen to learn . . . .

Letter B7

Vincent encouraged Milliet in his work and was impressed enough to write to Theo and ask him to send Cassagne's instructional book ABCD du dessin in order to assist with his tutelage of the young Zouave. Throughout the summer of 1888 Vincent van Gogh and Paul-Eugène Milliet spent much time together, exploring the countryside and discussing art. Van Gogh recalled one pleasant day:

I have come back from a day at Montmajour, and my friend the second lieutenant was with me. We explored the old garden together and stole some excellent figs. If it had been bigger it would have made me think of Zola's Paradou, great reeds, vines, ivy, fig trees, olives, pomegranates with lusty flowers of the brightest orange, hundred-year-old cypresses, ash trees and willows, rock oaks, half-broken flights of steps, ogive windows in ruins, blocks of white rock covered with lichen, and scattered fragments of crumbling walls here and there among the greenery. I brought back another big drawing, but not of the garden. That makes three drawings. When I have half a dozen I shall send them along.

Letter 506

Vincent enjoyed his time with Milliet, finding in him a friend that he could share ideas with. Still, the pair's relationship was somewhat turbulent--a frequent pattern accompanying Van Gogh's friendships. Early in his career, Vincent van Gogh enjoyed learning from his cousin by marriage, the painter Anton Mauve. Van Gogh very much valued their time painting together, but he was extremely sensitive to criticism and this had a detrimental effect on their relationship. Similarly, Van Gogh took great pleasure from his friendship with painter Anthon van Rappard, but they too would eventually have a falling out when Rappard criticized Van Gogh's first great painting The Potato Eaters.

The relationship between Van Gogh and Milliet would follow a similar path. In the Weiller interview Milliet described his disapproval of Van Gogh's technique (somewhat irrationally, given that Van Gogh's works had become very successful by the time of the interview):

What I find wrong in [Van Gogh's paintings] is that they are not drawn. He painted too broadly, he gave no attention to details, he never sketched out his design. Even though, (and I repeat,) when he wanted to, he knew how to draw. He let colour take the place of drawing, which is nonsense, because colour completes the design. And what colour . . . excessive, abnormal, inadmissible. Tones too hot, too violent, not restrained enough. You see, my friend, the painter has to make a painting with love, not with passion. A painting has to be "cuddled"; Van Gogh, he, he raped it . . . Sometimes, he was a veritable brute--"hard-assed," as they say . . . .

Still, Milliet maintained a pleasant friendship with Van Gogh right up until the time of his departure for Algeria. Milliet further commented: "He had faith, a faith in his talent, a somewhat blind faith. Pride. His constitution didn't seem to me very strong. But, on the whole, a good friend, not a bad guy . . . ."

The painting

The portrait above is a fairly straightforward study of the subject--very typical of similar portraits executed during Van Gogh's Arles period. It's likely that Van Gogh painted the work quickly because he lamented that Milliet "poses badly" (Letter 541a). Milliet is seen in his military uniform and wears a commemorative medal from his expedition to Tonkin. The background is a deep green of broad and forceful brushstrokes. The relatively plain background (plain, if compared with the more floral and ornate backgrounds found in, say, Portrait of the Postman Joseph Roulin from the same period). The only flourish is the star and crescent moon symbol seen in the upper right hand corner. This symbol was the coat of arms for Milliet's Zouave regiment and serves to further define the portrait's subject.

In gratitude for sitting for him and for delivering completed works to Theo, Van Gogh rewarded Milliet with a study (see Letter 561), but the fate of that study is unknown.

In comparison . . . .

Vincent van Gogh wasn't the only artist to portray a Zouave soldier in his art. For a comparative view, see the painting Portrait of a Zouave by Amedeo Modigliani.