Wheatfield with Crows

Appreciation

Wheatfield with Crows Nederland Vincent van Gogh Gallery and Appreciation

Introduction

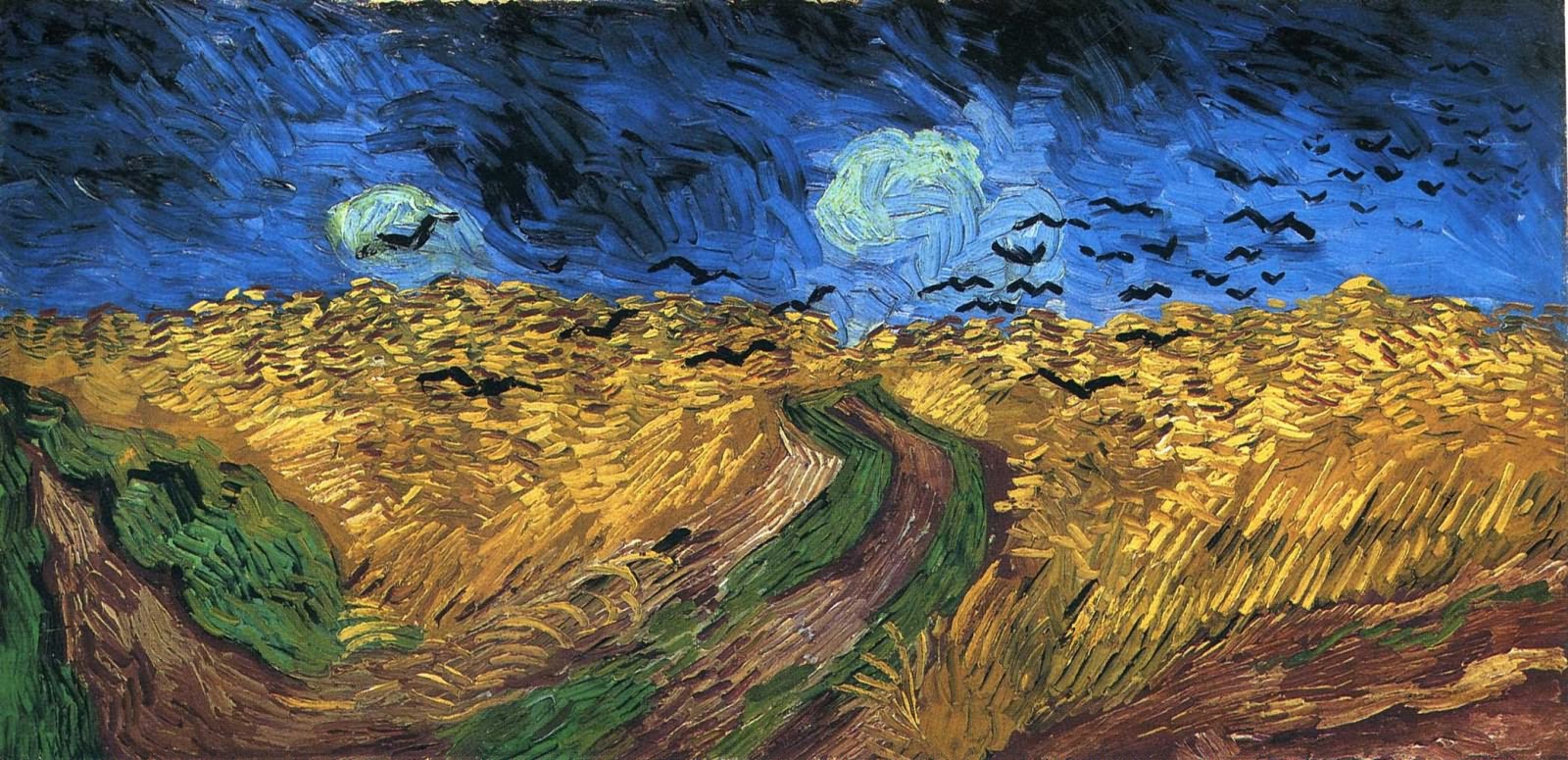

Wheat Field with Crows stands out as one of Vincent van Gogh's most powerful, and most fiercely debated, paintings. The many interpretations of this particular work are probably more varied than any other in Van Gogh's oeuvre. Some see it as Van Gogh's "suicide note" put to canvas, while others delve beyond a superficial overview of the subject matter and favour a more positive approach. And some more extreme critics cast their vision even further--beyond the canvas and the brushstrokes--in order to translate the images into an entirely new language of the subliminal.

Artistic analysis is, by its very nature, a subjective endeavour. Still, the most reasonable interpretations are best undertaken from a foundation based on facts.

Background

Contrary to popular myth Wheat Field with Crows is not Van Gogh's final work. Admittedly, it does make for a neatly wrapped interpretive gift if the painting really were Van Gogh's final work before his suicide. The painting is, without question, turbulent and certainly conveys a sense of loneliness in the fields--a powerful image of Van Gogh as defeated and solitary artist in his final years. Furthermore, both the popular films Lust for Life and Vincent and Theo rewrite history and depict this painting as Van Gogh's last--with more of an interest in dramatic effect than historical accuracy. As is ideally the case, however, an entertaining, though apocryphal, tale should be put to rest in the face of irrefutable fact.

Precise dating of Wheat Field with Crows is difficult because of its similarity to other works that Van Gogh was painting, and writing about, from the same period. In Letter 649, written about 10 July 1890, Van Gogh describes three canvases:

They are vast fields of wheat under troubled skies, and I did not need to go out of my way to try to express sadness and extreme loneliness. I hope you will see them soon--for I hope to bring them to you in Paris as soon as possible, since I almost think that these canvases will tell you what I cannot say in words, the health and restorative forces that I see in the country. Now the third canvas is Daubigny's garden, a picture I have been thinking about since I came here.

This passage presents difficulties. First because Van Gogh himself is writing in contradictions when he describes the works as conveying "sadness and extreme loneliness" on the one hand, but also "health and restorative forces" on the other. More significantly, one of the world's foremost experts on the letters of Van Gogh, Dr. Jan Hulsker, maintains that Wheat Field with Crows isn't even one of the three works mentioned by Van Gogh in this letter. Hulsker maintains that the former two works mentioned by Van Gogh in the quote above are The Fields and Wheat Fields at Auvers under Clouded Sky, whereas a number of other sources instead believe that the two works are, in fact, likely to be Wheat Field with Crows and Wheat Field under Clouded Sky. All four works fit in roughly with Van Gogh's own description of "troubled skies", but given that Van Gogh didn't provide specific details about the size of the works (calling them only "big") the speculation continues with no resolution in sight.

Regardless of the perplexities of which works are mentioned in Letter 649, Van Gogh scholar Ronald Pickvance in his book Van Gogh in Saint-Rémy and Auvers supports Dr. Hulsker's argument for an earlier dating of this painting with his own analysis of the letters. Pickvance explores the letters in depth and dates Wheat Field with Crows "contemporaneously from 7 to 10 July", more than two weeks before Van Gogh committed suicide. Finally, Hulsker puts the argument about Van Gogh's last works to rest by maintaining that they were ". . . Daubigny's Garden and Cottages with Thatched Roofs and Figures, both of which are far more likely to have been the last paintings [sic] he made."

Thus, given that Wheat Field with Crows is almost certainly not Van Gogh's final work, the "suicide note" interpretation should be cast aside. Still, there are many arguments to support the idea that the painting represents Van Gogh's own inner torment and despair. And for each of these arguments there are equally compelling counter-arguments to suggest that an opposite interpretation is just as valid.

Symbolic Interpretations

From a symbolic perspective it's worthwhile to review the basic elements of the painting and then explore each from vastly different interpretive ends of the spectrum.

The paths: It's not a difficult leap to symbolically equate the separate paths in Wheat Field with Crows with the paths, past and future, of Van Gogh's own life. The paths are basically comprised of three sets: two in each foreground corner and a third in the middle winding toward the horizon. The left and right foreground paths defy logic in that they seem to originate from nowhere and lead to nowhere. Some have interpreted this as Van Gogh's own ongoing confusion about the sporadic direction his own life had taken. The third, middle path has remained the most fertile for symbolic interpretation. Does the path lead anywhere? Does it successfully transverse the wheat field and seek new horizons? Or does it, in fact, terminate in an inescapable dead end? Van Gogh leaves it to the viewer to decide.

The sky: From his earliest years as an artist Van Gogh was fond of scenes involving stormy skies (see Beach at Scheveningen in Stormy Weather, for example). Van Gogh held a great deal of respect for the forces of nature and includes turbulent skies in a number of his works because the subject is so powerful and so full of artistic potential in the face of an empty canvas. Furthermore, Van Gogh once wrote about the liberating possibilities of storms: "The pilot sometimes succeeds in using a storm to make headway, instead of being wrecked by it." (Letter 197). Of course, as the years passed and Van Gogh's own mental state of well being became more battered, his perceptions toward nature may have darkened. Nevertheless, it can be argued that Van Gogh perceived storms as a vital and positive part of nature (admittedly, at least as he suggests in his earlier letters).

The crows: Perhaps the most powerful image within Wheat Field with Crows is that of the crows themselves. Again, much symbolic interpretation has sprung from the depiction of the flock of crows. Much of the speculation hinges on whether the crows are flying toward the painter (and, hence, the viewer) or away from him. If the viewer chooses to perceive the crows flying toward the foreground, then the work becomes more foreboding. If away, then a sense of relief is felt. The argument is flawed on two fronts.

First of all, as spirited and entertaining as the "flying toward / flying away" discussion might be, it's a point that will never be resolved. The truth is, there's no certain answer as to which direction, if any at all, the crows are flying. Much like "the chicken and the egg" argument, this point remains unsolvable and, consequently, moot.

Secondly, and more importantly, the interpretation of crows as harbingers of death is a completely artificial construct. And furthermore, one that Van Gogh, in his own writings, never appears to accept; on the contrary. Vincent van Gogh had a passion and a keen eye for all things in nature. As a result, his writings reflect an appreciation of, rather than a disdain for crows:

Last week, I was at Hampton Court to see the beautiful gardens and long avenues of horse chestnuts and lime trees, in the tops of which a multitude of crows and rooks have built their nests, and also to see the palace and the paintings.

Letter 70

I did see a great many crows on the Great Church in the morning. Now it will soon be spring again and the larks, too, will be returning. "He reneweth the face of the earth," and it is written: "Behold, I make all things new," and much as He renews the face of the earth, so He can also renew and strengthen man's soul and heart and mind.

Letter 85

Furthermore, Van Gogh was well aware of the effective use of crows within the works of other painters he greatly admired. In addition to a "magnificent" work by Giacomelli that used a crow motif (Letter R29), Van Gogh also admired the crows depicted in the works of Daubigny as well as the one painter Van Gogh revered above all others, Jean-François Millet (see Letter 136).

It would be foolish to dismiss the undeniably foreboding nature of the crows altogether, but the traditional interpretation of crows as symbols of death is too oversimplistic and conventional to apply to Van Gogh's approach toward Wheat Field with Crows.

Hidden Meanings . . . . .

Many people who favour symbolic interpretations of Vincent van Gogh's works have taken their analysis to another level. Over the years a number of writers have explored in detail the various symbols and images allegedly hidden within the subjects of Van Gogh's paintings and drawings. These images are claimed to be "hidden" visual messages within the works, perhaps intentionally created by Van Gogh (as a possible "message in a bottle" to perceptive future generations), or perhaps subliminal "whispers" Van Gogh unconsciously deposited into his own the brush strokes.

Wheat Field with Crows is a painting ripe for this sort of interpretation. Writer Yvonne Korshak analyzes the painting and reveals various images hidden throughout the canvas. These images include a giant bird filling the sky, a "cloud presence" and a Gabriel-like trumpeter within the clouds (shown in the detail at right). She explains:

In Van Gogh's canvases can be found the evidence of resolution on the plane of art of conflict between realism and imagination and between his aniconic Protestant conscience and his need to visualize images of salvation. Van Gogh's method of working includes the projection of spiritual longing through images that are merged with the natural landscape, and a fusing of realist and spiritual content.

Many people feel that interpretations like those of Ms. Korshak's open exciting, new possibilities. What secrets lie intermingled within the brush strokes? Are there truly images in Wheat Field with Crows that hint at revelations undiscovered for more than century? Perhaps a search of my own will yield some answers . . . . .

If one focuses specifically on the cloud bundle on the mid-right side of the sky, one can find a hidden image if this area is rotated 130 degrees counter-clockwise. The close-up of this image, shown at right, clearly depicts a left ear. Everyone familiar with the story of Vincent van Gogh is well-aware of the artist's mutilation of his left ear. What message was Van Gogh trying to convey by concealing this image within Wheat Field with Crows? What secrets does this previously undiscovered image reveal?

In a word, none. In order to illustrate my point that the whole pursuit of hidden images within Van Gogh works is a fruitless and unproductive undertaking, I went "treasure hunting" for these sorts of images myself. I merely turned the painting upside down and then scouted the sky for any potential symbolic representations. Within about five seconds an ear-like shape was barely apparent, but became more clear after rotating it to the proper angle. The truth is, far more time was spent cropping and rotating the image than in actually finding it. There is no "ear" within the sky of Wheat Field with Crows.

It's somewhat entertaining to speculate about such things, just as it's enjoyable to lay under a tree and search for elephants and dragons in the fleeting clouds of the summer sky. But to firmly maintain that Van Gogh deliberately hid subliminal images within his works is an effort in futility. Worse still, it's an endeavour that detracts from an appreciation of the overall work itself and, by the desperate need to see beyond the limits of the naked eye, it's a pursuit that is ultimately self-defeating.

Conclusion

The various interpretations of Wheat Field with Crows range from the simple to the absurd. Symbolic interpretation can be an often interesting, occasionally revealing, pursuit. But the potential of over-interpreting a work of art puts the viewer at risk of "missing the forest for the trees". The works of Vincent van Gogh provide the viewer with an incredibly complex and beautiful range of subjects to explore and to admire. His drawings are the product of a draftsman of indescribable skill and his paintings are always brilliant, often sublime. Viewers spending time searching for in-depth meanings within Wheat Field with Crows may be disappointed. For some, their unquenchable desire to understand the Van Gogh mythology better even sends them on a quest for hidden "holy grails" that don't exist.

Instead of seeking answers within Wheat Field with Crows, the viewer would find their time well spent if they simply admired the subject of this extraordinary painting: the colour, the vitality and the turbulent harmony of each and every brush stroke. The intangible secrets, if there are any, will continue to wheel in their own ineffable realm--like the crows.